TTAB Has Its First Precedential Decision of 2025

Audemars Piguet’s Bold Bid for Watch Trade Dress—Just Two Days In, the Verdict Becomes TTAB’s First Precedential Decision of 2025. Happy New Year!

1/31/20254 min read

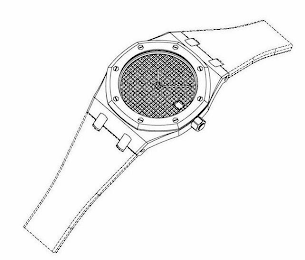

In a precedential decision, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the "Board") recently ruled on two trademark applications, 90045780 and 90045814, submitted by Audemars Piguet Holding SA. These applications sought to register the three-dimensional configuration designs of watches, emphasizing distinctive design elements such as the octagonal bezel with hexagonal screw heads. The decision sheds light on the legal principles governing product design trademarks, particularly concerning the functionality doctrine and acquired distinctiveness.

Audemars Piguet filed two applications under Section 1(a) of the Trademark Act, identifying the marks as three-dimensional configurations of watches. The applications were assigned to the same Trademark Examining Attorney, and their prosecution proceeded largely in parallel. The applications faced refusals based on lack of distinctiveness, functionality concerns, and drawing deficiencies. After multiple rounds of review, including a remand and several refusals, the Board finally rejected the applications. The rejection came 5 years after the initial filing and was based on two grounds: the functionality doctrine and the applicant's failure to prove acquired distinctiveness.

Under U.S. trademark law, a product design must not be functional to qualify for trademark protection. Section 2(e)(5) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(5), prohibits registration of functional features that are essential to a product’s use or purpose. In Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982), the Supreme Court established that a product feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or affects its cost or quality. This principle was further reinforced in TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23 (2001), which held that functional product features are not eligible for trademark protection because granting such rights would hinder legitimate competition.

To determine functionality, the Board applied the test from In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (CCPA 1982), considering factors such as the existence of utility patents, advertising statements highlighting functional benefits, availability of alternative designs, and the impact on manufacturing cost or ease. The Board also referenced In re Honeywell, Inc., 532 F.2d 180 (CCPA 1976), which found that widespread industry use of a design supports a finding of functionality.

The Board ruled that several elements of Audemars Piguet’s watch designs were functional and thus ineligible for trademark protection. These included the circular watch face, watch case shape, hexagonal crown, lugs, and linked bracelet. The Board found that these elements contributed to the effective operation, durability, and comfort of the watch, making them functional rather than indicative of source.

Under Section 2(f) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f), a mark may be registered if the applicant can prove it has acquired distinctiveness in the marketplace. The Supreme Court in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205 (2000), held that product design can never be inherently distinctive and must demonstrate secondary meaning through consumer recognition.

The Board examined whether Audemars Piguet’s advertising and sales established acquired distinctiveness. The applicant submitted extensive promotional materials, but the Board found that most advertisements prominently featured word marks like “Audemars Piguet” and “AP,” rather than highlighting the product design independently. The Board referenced In re Soccer Sport Supply Co., 507 F.2d 1400 (CCPA 1975), which held that advertising must explicitly direct consumer attention to a design element for it to acquire distinctiveness.

The Board also noted that Audemars Piguet’s “Royal Oak” collection encompassed multiple design variations, reducing the distinctiveness of any single configuration. The Board ultimately agreed that only the octagonal bezel and hexagonal screw heads had acquired distinctiveness, while the overall watch design did not establish secondary meaning.

A key procedural issue in the case involved the drawing requirements under Trademark Rule 2.52(b)(4), which mandates that functional or unclaimed features be shown in broken lines. The Board ruled that Audemars Piguet’s applications improperly depicted functional elements in solid lines, which suggested they were claimed as part of the mark. The Board required these elements to be depicted in broken lines to clarify that they were not part of the trademark claim. This ruling was consistent with In re Water Gremlin Co., 635 F.2d 841 (CCPA 1980), which affirmed that functional aspects of a product configuration must be depicted in broken lines to avoid claiming unregistrable subject matter.

The Board ultimately upheld the refusals to register the watch designs, concluding that:

The functionality-based drawing requirement was appropriate because most features were functional and could not be claimed as trademarks; and

The acquired distinctiveness-based drawing requirement was justified since only the bezel and screw heads had sufficient evidence of consumer recognition.

This decision reinforces several critical principles in product design trademark law. First, it affirms that functional features cannot be monopolized through trademark protection, even if they contribute to brand identity. Second, it underscores the importance of “look-for” advertising in proving acquired distinctiveness, as seen in In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116 (Fed. Cir. 1985). Third, it highlights that companies seeking to trademark product designs should carefully document consumer recognition and employ strategic advertising to strengthen their claims.

The Board's decision exemplifies the stringent requirements for registering product designs as trademarks. The ruling clarifies that companies must distinguish between functional and distinctive elements in their trademark applications and that acquired distinctiveness must be clearly demonstrated. This case serves as a critical reference for businesses navigating the complexities of product design trademarks and reinforces the balance between brand protection and fair competition in the marketplace.